A team of scientists working at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and led by Northern Illinois University physicist Zhili Xiao has created a new material, called “rewritable magnetic charge ice,” that permits an unprecedented degree of control over local magnetic fields and could pave the way for new computing technologies.

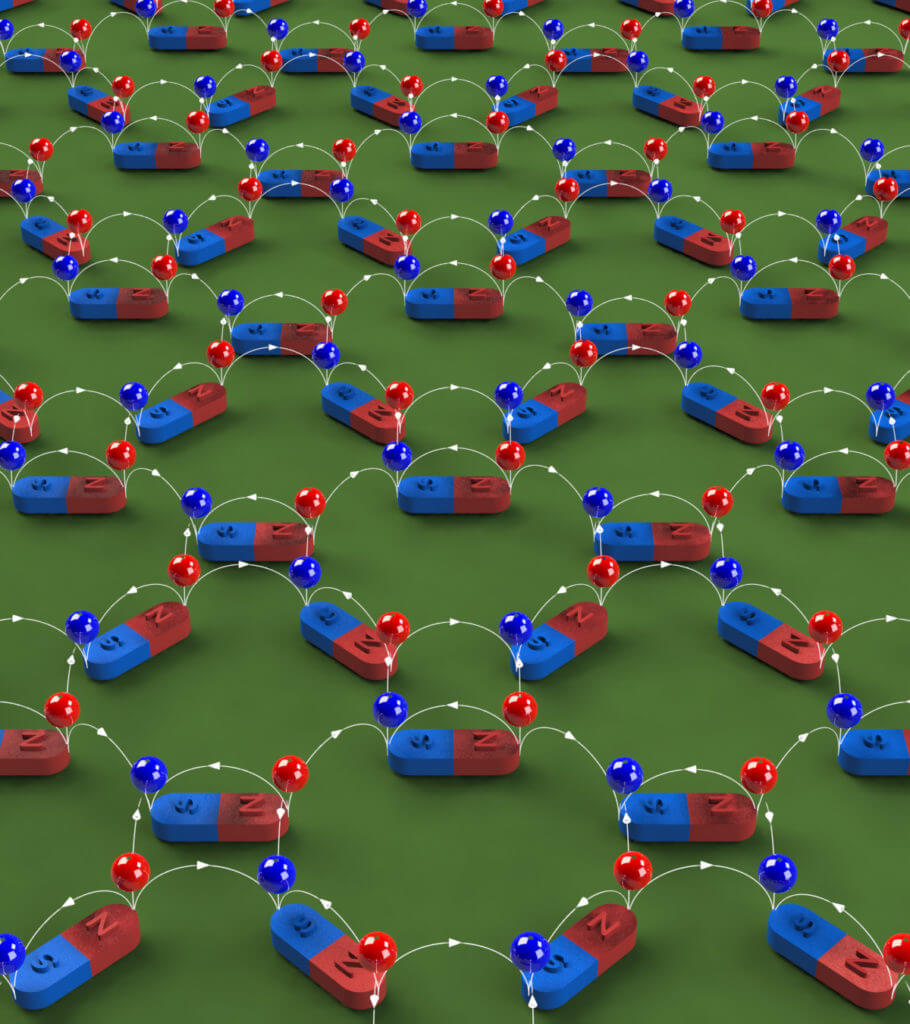

A depiction of magnetic charge ice. Nanoscale magnets are arranged in a two-dimensional lattice. Each nanomagnet produces a pair of magnetic charges, one positive (red ball on the north pole) and one negative (blue ball on the south pole). The magnetic flux lines (white) point from positive charges to negative charges. (Image credit: Yong-Lei Wang/Zhili Xiao)

The scientists’ research report on development of magnetic charge ice is published today in the prestigious journal Science.

With potential applications involving data storage, memory and logic devices, magnetic charge ice could someday lead to smaller and more powerful computers or even play a role in quantum computing, Xiao said.

Current magnetic storage and recording devices, such as computer hard disks, contain nanomagnets with two polarities, each of which is used to represent either 0 or 1—the binary digits, or bits, used in computers. A magnetic charge ice system could have eight possible configurations instead of two, resulting in denser storage capabilities or added functionality unavailable in current technologies.

A depiction of the global order of magnetic charge ice. Orange-red areas represent the positive charges; blue areas represent negative charges. (Image credit: Yong-Lei Wang and Zhili Xiao)

“Our work is the first success achieving an artificial ice of magnetic charges with controllable energy states,” said Xiao, who holds a joint appointment between the NIU Department of Physics and Argonne, where he is a materials scientist.

“Our realization of tunable artificial magnetic charge ices is similar to the synthesis of a dreamed material,” he added. “It provides versatile platforms to advance our knowledge about artificial spin ices, to discover new physics phenomena and to achieve desired functionalities for applications.”

Over the past decade, scientists have been highly interested in creating, investigating and attempting to manipulate the unusual properties of “artificial spin ices,” so-called because the spins have a lattice structure that follows the proton positioning ordering found in water ice.

Scientists consider artificial spin ices to be scientific playgrounds, where the mysteries of magnetism might be explored and revealed. However, in the past, researchers have been frustrated in their attempts to achieve global and local control of spin-ice magnetic charges.

To overcome this challenge, Xiao and his colleagues decoupled the lattice structure of magnetic spins and the magnetic charges. The scientists used a bi-axis vector magnet to precisely and conveniently tune the magnetic charge ice to any of eight possible charge configurations. They then used a magnetic force microscope to demonstrate the material’s local write-read-erase multi-functionality at room temperature.

An image produced by mapping the magnetic force of magnetic charge ice. Scientists were able to “write” in the field through control of the local charge of the material. (Image credit: Yong-Lei Wang and Zhili Xiao)

For example, using a specially developed patterning technique, they wrote the word, “ICE,” on the material in a physical space 10 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair.

Magnetic charge ice is two-dimensional, meaning it consists of a very thin layer of atoms, and could be applied to other thin materials, such as graphene. Xiao said the material also is environmentally friendly and relatively inexpensive to produce.

Yong-Lei Wang, a former postdoctoral research associate of Xiao’s, is first author and co-corresponding author on the Science article. He designed the new artificial magnetic ice structure and built custom instrumentation for the research.

“Although spin and magnetic charges are always correlated, they can be ordered in different ways,” said Wang, who now holds a joint appointment with Argonne and Notre Dame. “This work provides a new way of thinking in solving problems. Instead of focusing on spins, we tackled the magnetic charges that allow more controllability.”

There are hurdles yet to overcome before magnetic charge ice could be used in technological devices, Xiao added. For example, a bi-axis vector magnet is required to realize all energy state configurations and arrangements, and it would be challenging to incorporate such a magnet into commercial silicon technology.

But in addition to uses in traditional computing, Xiao said quantum computing could benefit from magnetic monopoles in the charge ice. Other potential applications of magnetic charge ice might include enhancement of the current-carrying capability of superconductors.

In addition to Xiao and Wang, members of the research team include Xiao’s Ph.D. student Jing Xu; scientists Alexey Snezhko, John E. Pearson, George W. Crabtree and Wai-Kwong Kwok in Argonne’s Materials Science Division; and scientists Leonidas E. Ocola and Ralu Divan in Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials.

The research was conducted at Argonne National Laboratory with funding from the DOE’s Office of Science and the National Science Foundation.