While much tornado research in recent years has focused on whether storm intensities and frequencies are increasing as a result of climate change, a new study by Northern Illinois University scientists points to suburban and exurban sprawl as the most prominent cause for alarm.

An aerial view of the damage caused by the 2013 tornado that touched down in Moore, Okla. Source: FEMA Photo Library.

The scientists say sprawl has created an “expanded bull’s eye,” or larger tornado target, increasing the potential for disasters of a magnitude or greater to the 2011 Joplin, Mo. catastrophe, which claimed more than 150 lives and injured more than 1,100 others.

“Let’s not miss the elephant in the room,” says lead author Walker Ashley, a professor of meteorology in the NIU Department of Geography. “The acceleration of development and sprawl results in an expanding bull’s-eye effect that will undoubtedly generate more frequent and higher impacts from tornadoes.

“Storm frequency and climate change are important topics, but how we develop as a society—how and where we build and live and spread out—is just as important in the construction of disasters,” he adds. “Because of sprawl, we’re increasing our odds of people being impacted, not just by tornadoes, but by any hazard. The big events we see on TV—such as the Joplin, Mo. and Moore, Okla. tornadoes—we’re going to see more of this.”

The study by Ashley and Stephen Strader, an NIU Ph.D. candidate in geography, will be published in an upcoming edition of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

Bigger tornado footprints

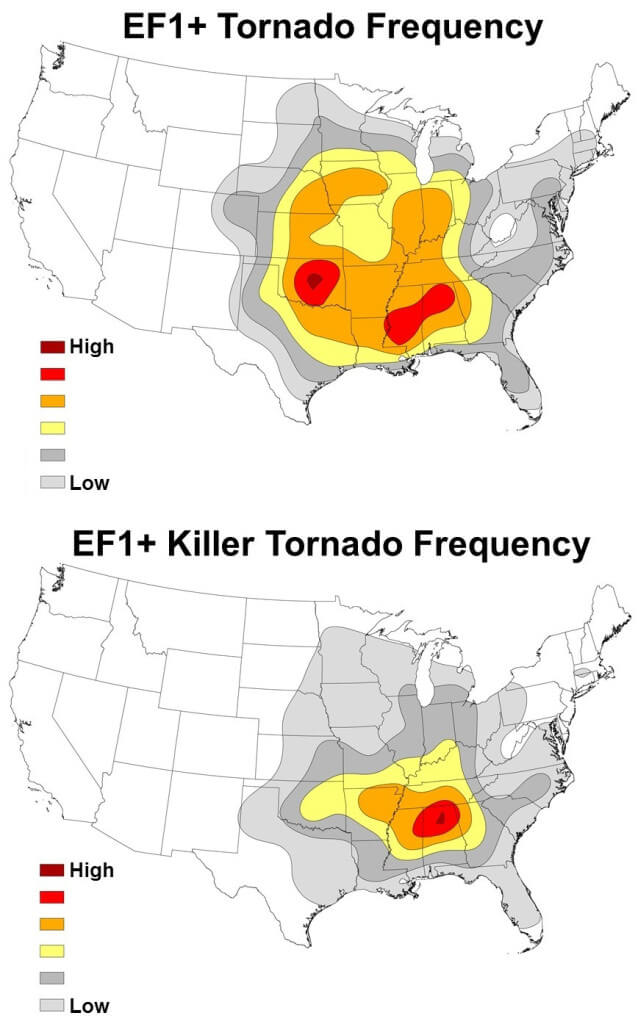

Contrary to what might be expected, it’s not the Central Plains’ “tornado alley” that is most vulnerable to tornado disasters but rather the mid-South and Midwest, the scientists say. The mid-South includes parts of Arkansas, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi.

Contrary to what might be expected, it’s not the Central Plains’ “tornado alley” that is most vulnerable to tornado disasters but rather the mid-South and Midwest, the scientists say. The mid-South includes parts of Arkansas, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi.

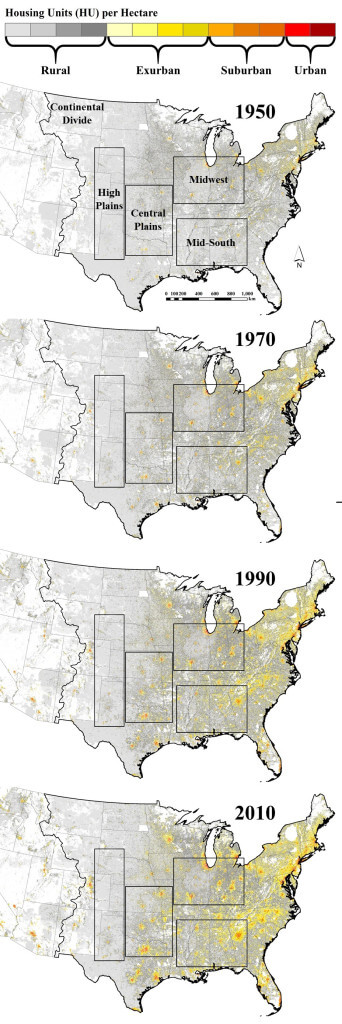

The researchers used data on housing growth, tornado frequencies and theoretical tornado footprints to illustrate how disaster exposure has increased in tornado-prone regions of the United States.

Footprints were calculated by multiplying a tornado’s estimated width by the length of its path of destruction. The study found that the mid-South region has the largest aggregate tornado footprint of all regions examined.

“While the Central Plains has a slightly greater frequency of EF1-plus tornadoes, the footprint of the tornadoes that do occur in the mid-South are nearly 28 percent larger,” Ashley says. “The mid-South’s propensity for cool-season events also suggests that tornadoes and their parent storms in the region will likely have relatively high forward speeds with a greater probabilistic threat to the landscape, including homes and businesses.”

Bigger tornado target

Between 1950 and 2010, the number of U.S. housing units increased by 98 million, or 377 percent. Most of the growth has been experienced in the exurban and suburban areas surrounding cities.

Between 1950 and 2010, the number of U.S. housing units increased by 98 million, or 377 percent. Most of the growth has been experienced in the exurban and suburban areas surrounding cities.

Of the tornado regions examined in the study, the mid-South has experienced the highest percentage growth in housing units—nearly 800 percent. The Central Plains region has had the second highest percentage increase at 472 percent.

“Our study shows the mid-South has the greatest overall tornado disaster potential because of the unique overlap of a relatively high tornado occurrence with greater amounts of developed land,” Ashley says. “These two disaster components are also evident in the region’s high tornado mortality.”

Tornadoes in the Midwest have smaller footprints than their counterparts in the mid-South and Central Plains. Yet the researchers say the region ranks second in overall exposure to disaster because it has more total housing units and sprawl than the Central and High Plains.

Tornado impact over time

To demonstrate the influence of sprawl on hazard dynamics, the scientists used three deadly tornadoes as case studies and modeled hypothetical damage trends for each tornado over time.

- The EF5 tornado that ripped through Newcastle-Moore, Okla., in 2013, damaging about 4,000 homes, would have impacted a tiny fraction of that in 1950—perhaps fewer than four dozen residences, the researchers say.

- The massive EF4 tornado that tore through Tuscaloosa, Ala., in 2011, damaging thousands of homes, would have affected roughly half as many residential properties in 1970.

- More than twice as many homes are now located in the path of the EF5 tornado that roared through Plainfield, Ill. in 1990.

“These comparisons underscore how growing populations and expanding development have led to greater tornado exposure and disaster potential,” Strader says.

“The mental image of a tornado dancing across a rural landscape is being replaced incrementally by the horrific views of real-life tornadoes devastating communities as the hazard increasingly interacts with amplifying population and development.”

Disaster mitigation

The April 9, 2015 tornado as it passes to the north of Ashton, Ill. Photo courtesy of Walker Ashley.

During the better part of the 20th century, annual tornado death tolls and mortality rates were in decline despite U.S. population growth. But beginning around 1985, the decline stalled, with mortality rates holding steady, or increasing in some regions.

“The stall is unnerving considering the rapid advancement of meteorology, investment in National Weather Service (NWS) modernization and development of new communication systems during this period,” Ashley says. “Mortality rates may be holding steady because of the growing vulnerability explained by the expanding bull’s-eye effect.”

The researchers note that their study has limitations. While it examined changes over time in the number of homes and people potentially exposed to tornadoes, other factors also can play significant roles in contributing to disasters.

“Tornado disaster severity is often dictated by such things as the quality of housing, daytime vs. nighttime tornado events and even cultural complacency,” Strader says. “We think all of these factors would be exacerbated by the expanding bull’s eye effect.

“We are hopeful our findings will initiate a dialogue among scientists, policy makers, emergency managers, city and regional planners and the public,” Strader adds. “The ultimate goal is to get stakeholders to implement disaster-mitigating land-use practices while building more sustainable and resilient communities.”

Related:

- What if April 9th tornado had taken different path?

- Deadly storms underscore new research finding

- Nighttime tornadoes are worst nightmare