Tucked away in labs on campus, students are quietly working to design small molecules to inhibit enzymes. Although that may not sound very exciting, the research could lead to new antibiotics, malaria cures, or even herbicides.

Since the 1980s, few new antibiotics have come on the market. Large pharmaceutical companies cut their investment in antibiotic research because it wasn’t profitable, says Timothy Hagen, a chemistry professor and lead investigator of the Northern Illinois University research project.

“Meanwhile, bacteria are changing and mutating and becoming resistant to the drugs that are out there,” Hagen says.

Through this project, NIU researchers have been at the forefront developing chemical compounds to fight infectious diseases. The research is a foundation for partnering with small and large pharmaceutical companies, he says, or it could lead to start-ups.

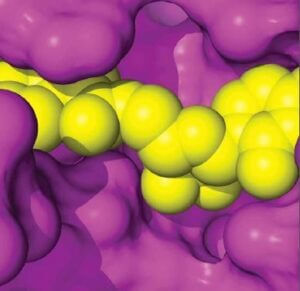

Professors Hagen, Rangaswarmy Meganathan, and James Horn have discovered small molecules that inhibit enzymes in a metabolic pathway that is shared by the malaria parasite, plants, and most bacteria. Compounds blocking the enzymes of the pathway could be used as antibacterial and antimalarial drugs, as well as herbicides, Hagen says.

Hagen works with students to design compounds, while Horn and his team of students determine whether the compounds inhibit enzymes. Then the compounds are given to Meganathan and his student, Debarati Ghose, so they can test them on bacteria. When a compound has proven to inhibit an enzyme, some students get to use the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory to see an x-ray of the atomic details of the enzyme.

Graduate students, undergraduates in a senior-level research course, and students in the Research Rookies program are assigned to a team.

Joy Blain, a graduate student majoring in chemistry, has evaluated molecules for their ability to inhibit enzymes that are essential in the bacteria that causes melioidosis, an infectious disease that is a potential agent for biological warfare. Melioidosis is primarily found in Southeast Asia and northern Australia, although it has occurred throughout the world, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since molecular binding interactions with an enzyme have been identified, the researchers can develop more potent molecules to fight the disease, says the 29-year-old native of Mahomet, Illinois, who has been involved with the research for two years.

“I think that having a broad knowledge of techniques used in studying these interactions will make me a better scientist in the future,” Blain says.

Senior Zak Lazowski worked as a Research Rookie with Hagen when he was a freshman. The Research Rookies program links freshmen, sophomores, and transfer students with faculty mentors in their major or area of interest to conduct a research project. Students from all colleges, departments, and majors can apply.

“Not many freshmen get a chance to do research, so it really set me apart,” says Lazowski, a DeKalb native. “And I think it helped me grow faster in the long run because I was exposed to it at such a young age and had time to think about everything.”

The biggest recognition for Lazowski is being listed as a co-inventor on applications for patents that NIU received for more than 100 anti-infective compounds. He smiles and speaks with excitement as he recalls creating a compound that had outstanding inhibiting activity against an enzyme.

Because of his work as a Research Rookie, the 21-year-old chemistry major decided that he wants to become a drug development researcher rather than a pharmacist. He plans to get a master’s degree in organic synthesis and a doctorate in medicinal chemistry.

And the experience helped him obtain an undergraduate research assistantship with Hagen last semester. Lazowski says Hagen is a great source of advice and has a personal interest in helping him succeed.

Those patented compounds were initially used to fight malaria, he says. NIU works with Washington University in St. Louis and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Maryland, to test compounds against malaria, an infectious disease that has become resistant to certain drugs.

“We’re able to demonstrate that some of our compounds do have antimalarial activity,” Hagen says.

NIU also submits compounds to Eli Lilly and Company to test against diseases, such as drug-resistant tuberculosis, diabetes, and illnesses of the central nervous system.

Hagen, who has 22 years of experience in the pharmaceutical business, began the research in 2010, when he joined NIU. At his previous job at deCODE Genetics in Woodridge, Illinois, he did research on protein crystal structures to study infectious diseases. After the business closed, he joined NIU to have the opportunity to do similar work.

Because of the progress made, NIU recently acquired a $356,000 grant for three years from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Whether drugs are invented by Northern or lead to pharmaceutical companies creating them, Hagen says, his goal is to move the process along to develop drugs that save lives.

“I got started on this because I’m passionate about helping people,” he says.

by Colleen Leonard

Originally published in the Winter 2015 issue of Northern Now