Mark Zuckerberg changed the way people share news stories and look up high school buddies when he founded Facebook. Now he and his wife might have changed how high-end philanthropy works as well, NIU professors say.

Zuckerberg and his wife, Dr. Priscilla Chan, will donate 99 percent of their Facebook stock to charity, an amount the New York Times estimated at $45 billion.

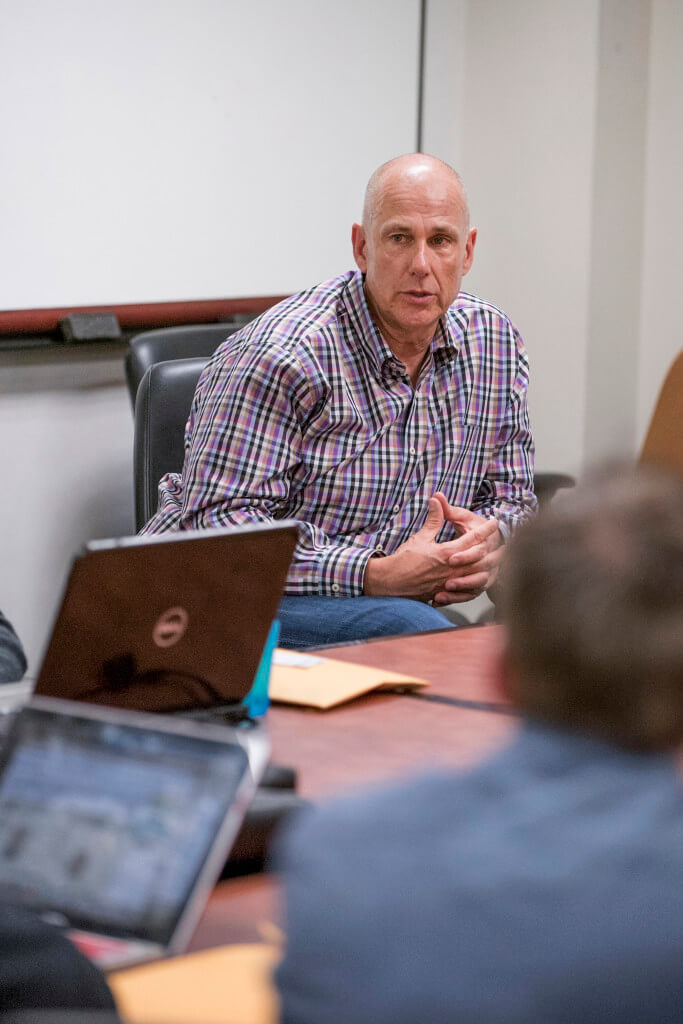

“Think about how many for-profit social businesses the Zuckerberg LLC will be able to invest in and launch,” NIU Management instructor Dennis Barsema said. “It’s mind-boggling. They have significantly altered the trajectory for scaling for-profit social businesses.”

Instead of setting up a foundation to dole out the gifts, the couple has decided to set up a limited liability corporation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, to manage their donation. Unlike fellow tech magnate Bill Gates’ nonprofit Gates Foundation, the Initiative will be a for-profit philanthropic organization.

“I think the traditional way to make a positive social change has been through the nonprofit realm,” said Christine Mooney, NIU’s Bill and Paula LeRoy Professor of Social Entrepreneurship. “I don’t think it’s a condemnation of nonprofits. It’s just not the only way.”

Mooney, who focuses her research on impact investing and social enterprise, said the general concept of setting up companies that do good for the world and well for the investors shouldn’t be foreign to people connected with NIU, home of the Center for Social Entrepreneurship. The center strives to not only teach them the skills needed to become social entrepreneurs, but also helps them develop the networks that can help them succeed.

“This has been going on for years. Environmentalists have been doing this, doing good for the environment but also making money,” she said. “People are looking at this and saying, ‘Can government do it all? Can nonprofits do it all? How can for-profit help?’”

The Triple Bottom Line

It’s called the triple bottom line, Mooney said: people, profit, planet.

Companies can choose any combination of the three. Patagonia, which makes high-end outdoor clothing, chose profit and planet. The company donates 1 percent of total sales or 10 percent of its profit, whichever is more, to environmental organizations.

California-based Toms Shoes went for profit and people, giving a pair of shoes to an impoverished child in a developing country for each pair of shoes sold, vision-based medical benefits for every pair of glasses sold and fresh water for every bag of coffee they sell.

But beyond the donation model, the companies’ core business also invests in good. Patagonia uses recycled materials. Toms has started moving some production to places their charities serve, bringing jobs to impoverished areas.

Toms’ profits might never match Nike’s, but the appeal is the “total return,” Mooney said. People looking to get behind a company, like Patagonia’s investors or Bain Capital, which purchased 50 percent of Toms last year, look at the benefits not only to their wallets but to the world around them.

Barsema is no stranger to investing in organizations he believes in. In 2000, Barsema and his wife donated the $20 million that built Barsema Hall, which houses the NIU College of Business, from which he graduated in 1977. The Barsemas also started scholarship programs at NIU, and Barsema currently teaches in the social entrepreneurship program there.

“Many social businesses have found it easier, and faster, to scale and grow their businesses by raising investor dollars, versus raising donor dollars,” Barsema said. “Donors are fickle. One year they give, the next year they don’t for a variety of reasons; employment changes, family changes, life changes.”

Although companies can mix and match the three bottom lines, Mooney warned that a company that looks toward people and planet without keeping an eye on profit won’t be around very long.

Students who are part of the NIU CAUSE club practice social entrepreneurship. Last year, they raised thousands of dollars for charitable causes by teaming up with a local business to make and sell pizzas at the business school.

A New Option

Perhaps burned by a $100 million donation to revamp Newark, N.J., public schools that resulted in community outrage, expensive consultants and no major improvements to students’ educations, Zuckerberg’s LLC will give him and his wife more control over where his funds go.

“If I invest in the right social for-profit business, I get my money back, I get a social return and now I have the money to recycle and invest in another for-profit social business,” Barsema explained.

The tradeoff is that Zuckerberg and Chan won’t get a $45 billion charitable deduction from the IRS in one lump.

“By using an LLC instead of a traditional foundation, we receive no tax benefit from transferring our shares to the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, but we gain flexibility to execute our mission more effectively,” Zuckerberg wrote in a Facebook post defending the couple’s decision. “In fact, if we transferred our shares to a traditional foundation, then we would have received an immediate tax benefit, but by using an LLC we do not.”

Barsema said the couple could receive tax benefits on the other end, when they transfer Facebook stock from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative to any 501(c)3 nonprofit they choose to fund along with the for-profit companies. The Initiative also can fund candidates and lobby in ways a nonprofit legally can’t.

“Being an LLC allows them to invest in political parties or candidates whom they believe can make significant positive change in the world,” Barsema said.

This freedom could make moves like Zuckerberg and Chan’s more attractive to other socially minded billionaires, Mooney said.

“I think we’re going to see a lot more of that,” she said.

By Paul Dailing